Fuzzy numbers from China, shifts in design and manufacturing, and more vertical slices are making predictions less reliable.

By Ed Sperling & Ann Steffora Mutschler

The inclusion of semiconductors in more products across more market segments—many of which historically have not been large consumers of chips—is having a big impact on how they are designed and manufactured, as well as how they are tracked and quantified.

In the past, semiconductor sales were so closely tied to the success of personal computers and smartphones that it was a fairly straightforward exercise to predict upturns and downturns and to prepare for market imbalances. In the case of smartphones, one application processor design could end up in more than 1 billion devices, with more than a dozen derivative chips to follow. But as those markets flatten, and as the overall picture is expanded to include new verticals such as automotive, industrial, consumer electronics and medical devices, as well as the broader IoT/IoE, the entire ecosystem surrounding chips is shifting.

Chips are being designed and produced in smaller batches with more customization, or as parts of systems that include software and other hardware. And they are being manufactured in more places, sometimes in regions that have never been tracked using older technology that is purchased on eBay or through non-traditional channels.

“There is now a much closer correlation between GDP and semiconductor sales,” said Falan Yinug, director of industry statistics and economic policy for the Semiconductor Industry Association. “We’re seeing semiconductors in more consumer goods and more markets, so if the overall GDP is growing, that translates into semiconductor sales.”

The SIA predicts chip sales will grow 1.4% in 2016 and 3.1% in 2017, a steady rise over the 0.2% growth reported in 2015, based upon statistics issued by World Semiconductor Trade Statistics. But one of the effects of chips being sold in more markets is there are more pieces to keep track of. The overall pie is bigger, but it’s sliced into more pieces, and those pieces can be affected by everything from supply chains to currency fluctuations.

Fig. 1: Estimated data growth in various categories, which in turn creates demand for more chips in more segments. Source: SIA

“One of the reasons we reported it was roughly flat year-over-year is that currency issues were impacting sales,” said Yinug. “Japan and the EU were two of the main sources for a lower final value of semiconductors. Total unit sales increased 3%, but the average selling price decreased due to the exchange rate, so the final value was flatter.”

In effect, this requires raising the abstraction level for economics. Gathering information from companies is always more accurate, but it’s also becoming increasingly difficult to separate out the raw data.

“It’s more than just semiconductors,” said Joanne Itow, managing director for manufacturing at Semico Research. “It’s also raw materials that are flowing into the channel and heavy equipment. All of that is causing a worldwide perception of a downturn. But some data is inconsistent or speculative.”

Case in point: While the SIA reports flat numbers, and an overall increase in chip unit shipments, others saw 2015 in a more pessimistic light.

“It’s clear we had a downturn,” said Risto Puhakka, president of VLSI Research. “The downturn was not very serious. It was not 20% down. It was reasonably mild. That’s a good thing. Whatever we’re going to get from the upturn is not going to be very strong. There’s no indication that we’re going to go to double digit growth rates in semiconductors. We are fiddling with between zero and five, and that’s not really exciting after a downturn.”

The flip side is that it is becoming increasingly pinpoint what’s happening when and where. That makes planning for everything from new chip designs to necessary manufacturing capacity much more difficult.

“We’ll probably see it in the sense that suddenly the majority of the companies report a positive quarter,” said Puhakka, who likewise points to the broad indicators for strength or weakness. “It’s not that the semiconductor industry will see a great quarter until those statistics start to improve, and there are more general economic indicators like commodity demand, or consumer spending, or world GDP, China GDP — things of that nature. As those things rise, we would probably see significant improvement in the semiconductor industry.”

The China factor

One of the biggest question marks in all of this is China, which now consumes about 45% of the world’s semiconductors for internal use and for exports, according to a McKinsey & Co. report.

From a top-line perspective, GDP forecasts are down slightly for China. According to World Bank forecasts, the country’s GDP will drop to 6.7% growth in 2016 from 6.9% in 2015. The International Monetary Fund put the growth number at 6.3% for 2016, and 6.0% in 2017. Moreover, the IMF warned that China is experiencing a “faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports, in part reflecting weaker investment and manufacturing activity.”

That’s still nearly twice the global growth projection of 3.4% in 2016 and 3.6% in 2017. But the picture is more complicated than the top-line numbers indicate. The yuan has been falling against the dollar. While that makes Chinese labor and exports cheaper, it also makes imports more expensive. McKinsey estimates that 90% of the chips used in China are imported, although a sizeable portion of those are again exported in finished products.

This is one of the reasons China has been so actively pursuing acquisitions and strategic investments outside of its borders. It clearly needs to build up its technical and manufacturing capabilities in order to reduce its imports. According to The New York Times, over the past 18 months Chinese companies and individuals have moved about $1 trillion out of China. All told, China’s currency reserves dropped to $3.2 trillion in January from a high of $4 trillion in June 2014. How much of that was used to prop up the country’s currency is unknown.

Some of this currency swapping reflects an increase in M&A. Some also reflects falling confidence in the yuan, as exemplified by a Jan. 4 selloff on the Shanghai exchange that triggered circuit breakers to halt trading. But it also may be a case of too much focus on some markets and not enough on others.

“Everybody is interested in China,” said Puhakka. “I haven’t been in a meeting with a customer when we haven’t had a discussion about China one way or the other. There are a number of things that are taking place. There’s the plan to spend a significant amount of money on a yearly basis for a number of years, and then the questions come about what happens if they are successful. Are their plans real? What about their economy slowing down? How does that impact things? There are a number of things that come into play, and there are a couple of things that are safe to say. China will have a more significant role in the semiconductor business in the future years. They have a large domestic market for electronics goods and services, which they like to serve from their domestic sources. Also, there are significant challenges. One is the economy. The other is IP. Those are very well known. At the same time, China is viewed at a significant wildcard at this point, and this does cloud forecasts, so there is a great deal of fog on the horizon.”

Design/manufacturing shifts

Along with these uncertainties, approaches to designing chips are changing. They are becoming more customized for narrower market slices, using more limited foundry runs or multi-project wafers (MPWs), which are much harder to track.

“We see a growing MPW business,” said Mike Gianfagna, vice president of marketing at eSilicon. “That includes everything from 28nm to 500nm, with 16nm interest on the rise. Many of these designs are single runs, fueled by new chip designs in the commercial sector and semiconductor research in the academic sector. We are seeing a growing segment of our customers that are using MPWs for low-volume production, however. New market validation and small market segments are both driving this. We expect to see this trend grow.”

Further clouding this picture is a subtle but significant shift in sales and marketing. Rather than just selling chips to systems companies or OEMs, or designing to specs for a socket on a board, the emphasis is on market-specific solutions that incorporate hardware, software and relevant IP.

“In a Micron presentation earlier this month, they were clear this isn’t just a commodity business anymore,” said Semico Research’s Itow. “It’s somewhat IoT-driven. Companies are developing new products that initially will not be sold in huge volume. We’re expecting there will be big winners and losers in this.”

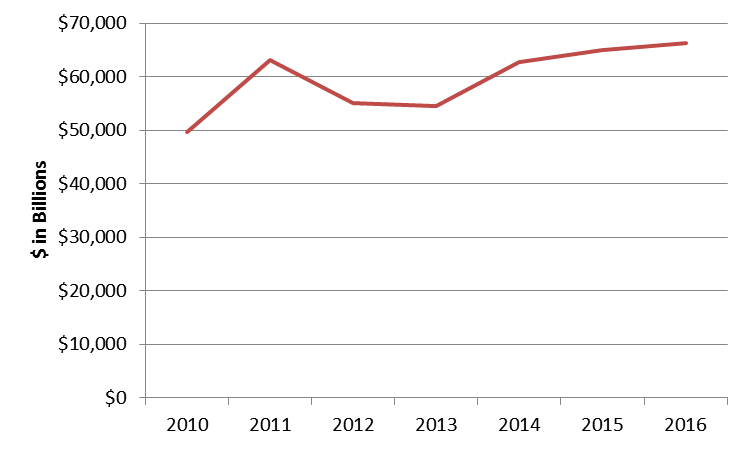

Fig. 2: Total semiconductor capital expenditures, 2010-2016. Numbers were down 3.1% in 2015, with an expected increase of 1.4% in 2016. Source: Semico Research.

There also will be new strategies for getting to market more quickly based upon pre-developed IP, subsystems, platforms, assembly strategies based upon reference designs and advanced packaging such as fan-outs and 2.5D. While it’s easy to say that an SoC is one chip, how many chips is a fan-out or 2.5D package? At this point there are no clear answers, and it may not be so easy to define chips again—ever.

The currency ruined last year,odd that everybody is talking about it but nobody is doing anything about it. The USD doesn’t have to be the currency everybody works in, it’s not that hard to find a better solution. It worked ok before globalization but now working in any single currency is a permanent risk. Hedging is fine but not good enough. Can’t say i have a clue about currency this year but China has been spending a lot of it’s reserves to try to keep the CNY from falling but they won’t be able to keep doing that for too long.

The upturn is not going to be much this year because the cause of the downturn is still there, those currencies haven’t bounced back. You still have high end phones retailing for 40-50% more in those markets than what they used to be. As specs go better and people need to upgrade sales will pick up a bit but there is no upturn really,for that, currencies would need to actually recover.

China in phones is rather odd, there might be a big risk there at some point. If you look at the installed base vs phone sales, the refresh cycles seem to be very very short compared to the other markets. 100-150$ smartphones have reached some incredible levels of performance and quality, the Chinese consumer might mature a bit (and not feel social pressure to upgrade to the latest model every year) and there could be a major impact on refresh cycles soon. As an upside, penetration in rural (almost half the population) is very low but better 3G/4G coverage and much much cheaper data are needed in rural for things to get moving.