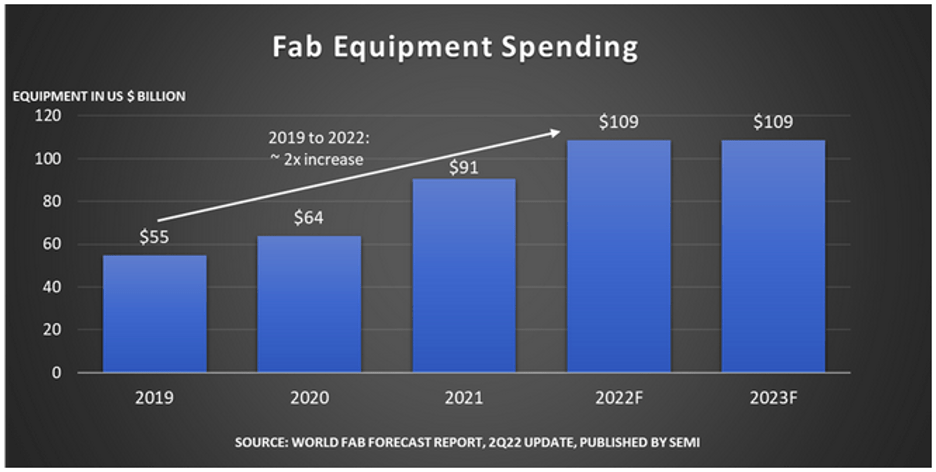

Total could reach $109 billion this year. What does that mean for the chip industry?

Corporations and governments around the globe are making record-breaking investments in chip manufacturing plants amid a major push to make the semiconductor supply chain more robust and less prone to shortages caused by everything from market variations to geopolitical interruptions.

These investments — which range from updating existing fabrication facilities to building entirely new fabs from the ground up — could reach a total of $109 billion this year, according to SEMI. That number is an all-time high for the semiconductor industry, and a 14.7% increase from last year. SEMI tracks more than 1,400 facilities and lines around the world, including 133 facilities and lines planned for the future.

Over the past three months alone, chipmakers announced a new multi-billion dollar fab jointly operated by STMicroelectronics and GlobalFoundries in Crolles, France; an approximately $650 million investment by Renesas to reopen a fab in Tokyo, Japan; and the groundbreaking of a fab in Sherman, Texas by Texas Instruments that represents an investment of up to $30 billion, among many others. In addition, Samsung filed tax paperwork showing it is considering investing up to $200 billion in new fabs in and near Austin, Texas.

The surge in activity comes at a tumultuous time for the industry. Chip companies are simultaneously grappling with the lingering impacts of the pandemic while steadily heading toward a $1 trillion-plus future. Semiconductor experts know the field is cyclical in nature and that fabs require major outlays and long-term horizons. The current situation presents a disjointed narrative for corporations seeking industry-friendly laws and public funding for their projects, and so advocates have branded the projects as fulfilling a wide range of ambitions.

There are those who emphasize that the fabs will bring jobs to areas that need them, tapping into labor pools that might help ease the talent crunch companies have complained about for years. Others say the ventures are insurance against future chip and wafer shortages that have disrupted medical device manufacturing, upended the auto supply chain, and created security risks with substituted parts.

In his March testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, Lam Research President and CEO Tim Archer summed up the issue as the need to create “a secure and resilient supply of semiconductors while also accelerating innovation ahead of the rapidly evolving technological complexity.”

The projects are not without controversy. In the U.S., a $52 billion legislative package of industry subsidies known as the CHIPS Act is mired in partisan politics and concerns about the equity of the bill. Some critics have said the goals of such bills are too wide-ranging to be coherent. The Senate passed a procedural bill this month that may lead to official approval. The turmoil over the legislation has led to Intel delaying a fab groundbreaking in Ohio, and GlobalFoundries says it will delay plans for a fab in New York if the measure fails to pass.

Fig. 1: Global fab equipment spending is expected to reach $109 billion this year. Source: SEMI

The European Chips Act, which was introduced in February, would put more than €43 billion in public and private investments toward various aspects of strengthening the semiconductor ecosystem. The measure is currently being discussed by the EU’s member states and European Parliament.

As comprehensive as they are, the two Chips Acts pale in comparison to the state investment taking place in China. The Chinese government aims to have a fully self-sufficient semiconductor industry as part of its Made in China 2025 strategy. To that end, the country has created a $170 billion investment fund used to fund companies and build fabs.

Sanjay Malhotra, vice president of corporate marketing at SEMI, said the industry’s market dynamics are nuanced and defy easy explanation. But the recent wave of investment seems less like a blip than a harbinger of the future, he said. After all, the rapid pace of innovation within the field comes hand-and-hand with the need for investment.

“It’s what the industry is all about. You decrease the cost of the transistor only when you upgrade the equipment,” Malhotra said. “It is a logical thing. Let’s say you set up a new fab today with the technology of 5nm. With Moore’s Law, a few years down the road that technology has to be replaced with 3nm because you have to keep decreasing costs. All these fabs are coming online, and two or three years down the road they will be replaced as the industry moves on to the next technology.”

Malhotra said that the short-term chip demand generated by a pandemic-related surge in consumer goods spending is a moving target that doesn’t speak to the long-term needs of the industry. “We don’t expect the demand generated by work-from-home activities to continue,” he said. “More important are the worlds of IoT and auto. Tesla, for example, is a computer on wheels. Autos have big data, and then there needs to be a data center to process all the data that is generated. In terms of size, computing and smartphones command the biggest chunk as a percentage of the total semiconductor consumption currently, but IoT and auto are where it is going.”

Malhotra also pointed to medical technology, aerospace, and quantum computing as areas that will drive the industry forward in the coming years.

From a geographic standpoint, fab equipment spending is being led by Taiwan, Korea and China, with the Americas in fourth place, according to SEMI. While investment in Europe and the Mideast is small compared to Asia, the rate of growth is notable — 176% year-over-year.

Capacity is expected to increase 8% this year, and next year the industry is expected to churn out the 200mm equivalent of 29 million wafers per month. The majority of equipment spending this year will come from capacity increases at 158 fabs and production lines, SEMI says. The sectors that will account for the largest capacity increases this year and next are foundry and memory.

The impact of these changes runs wide and deep. For a materials and processes company like Brewer Science, for example, the current market and investment dynamics mean communication with clients is even more important than in the past. “It is critical to work closely with these companies to understand the forecasted product mix so we can reinforce an already stretched supply chain,” said Tom Brown, executive director of the semiconductor business unit at Brewer. “Balancing between existing commercial products and improvements versus intersecting fab start-ups and qualifications with our new technology solutions can put significant pressure on our R&D teams as they work to meet all of the requests.”

Srikanth Kommu, executive vice president and COO at Brewer, said the company has “strategically invested to grow along with the industry.” “Even at the height of the Covid pandemic, we had the capacity, systems, and supply chain in place to continuously meet and exceed our customers’ demand.”

Materials are a critical piece of the puzzle, and the chip industry knows it. The only rare-earths metal and magnet manufacturing facility in the United States — appropriately named USA Rare Earth LLC — opened earlier this year amid China-U.S. trade tensions. Of primary concern are light rare earths like neodynium and praseodymium, which give magnets their magnetic properties, and heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium, and are used to prevent magnets from demagnetizing at high temperatures, according to Thayer Smith, president of USA Rare Earth.

“If you look at your iPhone or iPad, there are something like 90 rare earth magnets in those,” Smith said. “An F35 fighter jet has 900 pounds of magnets in it. A Virginia-class submarine has 9,000 pounds. You’ll find them in any kind of high-performance motor, and what’s really driving the market is electrification of the vehicle fleet. But they’re also used in refrigerators, HVAC systems, and consumer electronics. They’re ubiquitous. If you don’t have a rare-earth magnet, you can’t ship an electric vehicle.”

It takes an end-to-end supply chain to create a final product, and disruptions in any segment can have broad consequences in other seemingly unrelated areas. “We’re seeing big delays with some of our laminate substrates,” said Rosie Medina, vice president of sales and marketing at QP Technologies. “We have a 52-week lead time on one quote. We’re three months into that, and customers are waiting patiently. One ceramic package company isn’t even taking any more orders. They kept sending me lead times that were so long that they finally said, ‘No more, stop.’ And this is on older legacy-type packages. Leadframes for our QFNs (quad-flat no-leads) have gone from about 8 weeks to about 16 weeks, which we don’t consider too bad in comparison.”

Those kinds of stories are echoed across the chip industry, and the industries that require semiconductors. But that’s only one challenge among many. Companies across the industry will have to address is how to find a sufficient number of qualified workers for existing and new fab ventures. Semiconductor companies have pointed to a variety of factors over the years to explain their staffing problems, including K-12 educational issues and some potential employees shunning the hardware ecosystem for software jobs at tech giants. Now, many of those tech giants are integrating their hardware and software operations, creating even more competition for the same job candidates in the short term.

Malhotra said the issue has reached a critical juncture. SEMI estimates there is a shortage of about 80,000 workers in the U.S. alone, across multiple job functions. Over the next decade, the U.S. will need anywhere from 500,000 to 750,000 additional workers in the semiconductor ecosystem. “You can have a fab, you can fill it with equipment, but if you don’t have the people to run it, what’s the point?”

Industry experts say the solution to such issues will require a multi-pronged approach, which may include educational investments, more diverse and inclusive hiring practices, and helping some of the thousands of people who leave the military each year transition to semiconductor-related jobs.

Those new workers increasingly may be headed toward new fabs instead of existing fabs with expanded capacity, as Malhotra says it is possible that the mix of investment will move toward new facilities in the coming years. He noted the fab investment landscape could create opportunities for new entrants into the industry, as well, though not necessarily new fab owners — at least in the U.S. and Europe.

“It costs so much to make a fab, something to the tune of $10 billion, and that’s a lot of capital to raise for a startup,” said Malhotra. “But there’s no reason why a bunch of engineers can’t get together with funding and have a design startup or a fabless company. That activity is happening and will continue, especially with all the new applications which need innovation. But I doubt you will hear about someone coming out of the blue and starting a fab on the U.S. and European side. Where you may see that kind of activity is when the government funds and creates new players in places like India, like has already happened in China. In India, there are quite a few established industrial houses that have capital and talent, and the government could incentivize them with land or a tax benefit. That’s how new names could crop up.”

Conclusion

As the response to the U.S. Chips Act shows, public subsidies for chipmakers can be controversial. But it’s not just skepticism and political maneuvering that is delaying fabs. The economy is slowing as well, and it is unclear how that dynamic will impact fab investment across the industry.

Economic concerns already have caused at least one company to change its fab investment strategy. SK Hynix reportedly decided to delay a final decision on a $3.26 billion new production line as a result of concerns about inflation and decreased demand.

Whether or not other chipmakers will make similar decisions remains to be seen.

–Ed Sperling contributed to this article–

Related Stories

Wafer Shortage Improvement In Sight For 300mm, But Not 200mm

Leave a Reply