Why the latest round of acquisitions is causing angst in the semiconductor industry.

The recent spate of industry consolidation continues to have repercussions across the semiconductor industry. Some of those effects will subside once the deals are either approved or nixed by regulatory agencies. Others will raise questions for months or years to come.

Consolidation is not a new trend in the semiconductor industry, but the pace and size of the acquisitions in the past year are unparalleled. Spurred by cheap capital and the expected rise of interest rates at the end of this year, companies have gone on a buying spree. The argument is that acquisitions—and subsequent spin-offs or sales of non-strategic assets—allow companies to quickly strengthen their position in core markets and position themselves for new ones that have opened, or which are expected to open, as a result of increased connectedness with the Internet of Everything.

Below is a list of the biggest deals announced over the past 12 months and their status. Of the eight largest, only two have been finalized so far. While that may indicate business as usual until these deals are consummated, the reality is that nothing operates at the usual speed during the approvals process. Expenditures and plans are often delayed or even scrapped. Moreover, the larger the acquisitions, the more approvals that are necessary by government agencies in countries in which they do business.

Fig. 1: The largest M&A deals in the semiconductor industry. Source: SEC filings and company reports

The disruption continues well after the deals are finalized, too. Integrating large companies is more difficult than acquiring the engineering resources or IP of a smaller company. While there are market synergies and economies of scale, combining internal processes and meshing cultures is difficult at best, and sometimes impossible at worst. For one thing, there is more of everything in larger companies—more people, more business units, more displacements. For another, most large companies have made numerous acquisitions of their own, and not all of those are fully integrated.

That’s just the internal side. The outward-facing combined company may be a customer, a partner, or a competitor, or a combination of all three. It takes time to digest exactly what the combined companies require going forward in terms of tools and equipment. Will they pay the same rates, or will they demand deeper discounts because of a shrinking market and greater buying power?

“The principal difficulty we see is not the long-term effect,” said Wally Rhines, chairman and CEO of Mentor Graphics. “Long-term, there will be little or no impact on EDA. Short-term, there is a lot of uncertainty. If you don’t know the size or strength of the company, you’re generally less aggressive about renewal commitments. Historically, M&A has had only a temporary effect on the semiconductor industry. That could be measured in years, not months, but semiconductor R&D as a percentage of revenue for the industry is 13% to 14%, and that number has been constant over 32 years.”

Rhines said companies may reduce their R&D short-term during the integration process, but over the long term if they don’t reinvest at that historical average percentage they are taking a significant risk.

Still, it may be a bumpy road in the short term. Mentor just reduced its sales forecast for Q4, partially attributing that to consolidation among its customer base. It’s unlikely Mentor will be the only EDA company to feel this pinch, but it’s hard to tell exactly how this will play out. The Big 3 EDA companies, in particular, are so diversified that their businesses no longer look like mirror images of each other. Mentor is betting heavily on automotive design software, while Cadence has pushed heavily into IP. And Synopsys has branched out into software utilities and a wide swath of IP ranging from processors to embedded memory. Likewise, some smaller companies are in niches that will be relatively unaffected, while others may be impacted to a much greater degree.

Market shifts of this magnitude make forecasting difficult. Sometimes consolidation works to a company’s advantage, while other times it doesn’t.

“Consolidation has rubbed us both ways,” said Anupam Bakshi, CEO of Agnisys. “In one instance a customer acquired an additional license because their company got acquired by another company that was already a customer. On another occasion, a potential customer had to delay the purchase because the new parent company had to approve the purchase. But certainly, consolidation has reduced the number of potential customers. The selling cycle is a bit longer on average than last year.”

Like most executives, Bakshi believes the consolidation will be good for vendors and their customers. “If anything, consolidation may induce a ‘limbo’ period on the sales process as projects and resource requirements get re-examined. On the other hand, existing business in one of the companies being merged may assist reaching users elsewhere in the other entity being merged.”

A report by PricewaterhouseCoopers drew a similar conclusion. It said the key to developing successful IoT strategies will be based on four criteria:

• Resource augmentation;

• Access to new markets/customers;

• Increased market share, and

• Increased market power.

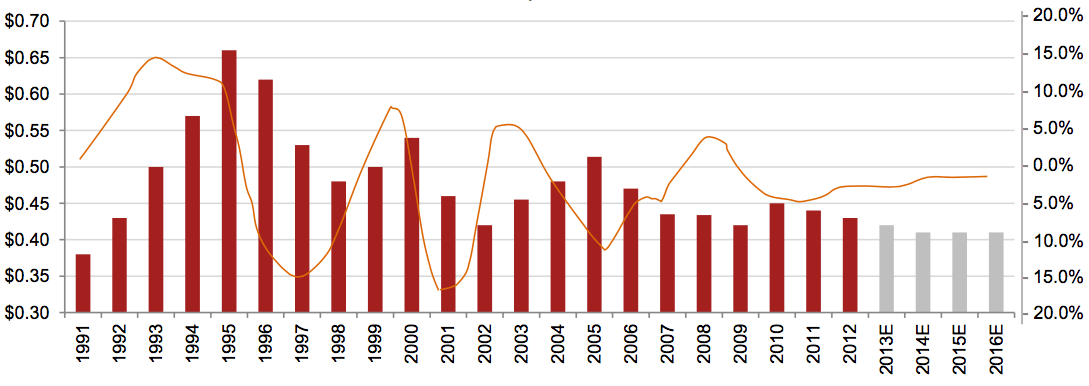

That report also charted a decline in average selling prices, which is another driver for consolidation.

Fig. 2: ASP Trends. Source: PwC, based on data from SIA and RBC Capital Markets.

Throughout the industry, there are widely mixed reports of the effects of consolidation. As Charlie Janac, Arteris chairman and CEO, noted: “IP companies are neutral.” He said that’s particularly true for royalty models, where the number of licenses or projects may or may not shrink, but the net effect is minimal.

Ecosystem questions

What’s become apparent, particularly with ARM‘s success in the smartphone market, is that ecosystems can be more effective than a single-supplier strategy. While Intel was extremely successful in the PC era in branding itself with an “Intel Inside” campaign, ARM effectively closed Intel out of the mobile phone market using an embedded processor strategy.

Those ecosystems arguably are even more critical in markets, where the potential is so enormous and the pieces so varied and interconnected that it’s uncertain what is required to attain a dominant position in any slice. Market consolidation adds complications to the ecosystem picture.

“There are a lot of negatives to consolidation, even though it ultimately can be positive,” said Mike Gianfagna, vice president of marketing at eSilicon. “Traditional ASIC suppliers are becoming part of bigger companies, and the larger the company the more focused they have to be and the more rigid the business model. They need to get everyone into the same mold.”

This is why big companies have been so successful in the technology world—they are very focused and process-driven. That’s the reason why reason why startups have been so successful, too. They can move more quickly and freely without those kinds of rigid processes to tap new opportunities that big companies can’t get to quickly enough or don’t care about.

“The challenge is when combined companies compete with their own customers,” said Gianfagna. “That also opens up new opportunities with new and different combinations. So large ASIC vendors are now looking around and figuring out who has done advanced designs at 28nm and below, for example. We’re now finding we’re in the running with some very large companies that we never competed against before, and it’s having a very positive outlook on the future.”

As the total number of buyers of technology decreases, there also is a possibility that the value of what they’re selling will rise—and the value of what they buy to make those designs possible will increase along with it.

“In many markets, a smaller number of players is healthier,” said Drew Wingard, CTO of Sonics. “But in the past, the semiconductor industry has been its own worst enemy. There are very few companies today that are able to monetize design. But with this round of consolidation, that could finally change. The total number of buyers is decreasing. Now the question is how long it will take for the value to go up.”

More to come

Perhaps the biggest unknown is China, where more than $120 billion is sitting on the sidelines. At least part of that will be used for acquisitions. China consumes nearly 60% of all semiconductors and imports about 90% right now from foreign suppliers, and right now it has about a $150 billion trade balance just for IC imports, according to Gartner.

The only way to close that trade gap quickly is through acquisitions and strategic investments. Tsinghua Unigroup’s $23 billion bid for Micron in July was the largest on record so far. That deal has not gone through, ostensibly due to government concerns. Much of this M&A activity in the United States is kept quiet because it requires review and approval of U.S. Committee on Foreign Investment, a secretive Treasury Department unit that is shielded from public inquiries due to national security concerns. In the wake of its initial bid, Tsinghua reportedly is in talks with Micron about a joint fab.

There are six major government-backed funds in China, according to a just-released McKinsey report—The Sino IC National Fund, plus city-based funds in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Xiamen and Hefei. How those investments will fare outside of China will depend upon everything from relations between China and various governments, the overall economic picture, and whether companies are deemed critical to national interests.

Perhaps even more telling, according to the report, is that to meet the “Made in China 2025” goals, all new foundry capacity added through 2025 will have to be in China.

Source: McKinsey & Co., based upon IHS application market forecast tool and McKinsey analysis.

Conclusion

There is no question that industry consolidation will continue to cause disruption on a global scale. At times, that will involve blips in sales. Last month, the Semiconductor Industry Association reported a Q3 increase of 1.5% compared with the previous quarter, down 2.8% year over year. Part of that overall market softness was due to currency devaluation, and part of it was companies burning through their inventories in the wake of uncertainty.

Consolidation is just one component in this picture. It’s certainly an important one, and it raises many unanswered questions about how the industry ultimately will look when the dust settles. But it may pale in comparison to the upheaval caused by the Internet of Everything, the mashing together of different markets that rarely or never interacted before, and the flattening of some high-growth markets such as smart phones and tablets.

Related Stories

The Price Of Consolidation

Consolidation Hits OSAT Biz

Consolidation And Innovation

Fundamental Shifts In Chip Business

Lam and KT are also merging- and TEL and AMAT tried to merge. They are part of the Semi industry as well- though the other end of the supply chain.

Thanks for the comment. We agree, and that’s the subject of a separate story. Consolidation in the equipment space will have some interesting effects.

Absolutely. And in that space, the impact of consolidation could have very far-reaching effects on price and time to market.

You’ll know we’ve made progress if you’re down to one remote control in your living room and it works for every device.