Experts at the table, part 2: Where EUV fits, what problems still remain, and what are the alternatives.

Semiconductor Engineering sat down to discuss lithography and photomask technologies with Gregory McIntyre, director of the Advanced Patterning Department at Imec; Harry Levinson, senior fellow and senior director of technology research at GlobalFoundries; David Fried, chief technology officer at Coventor; Naoya Hayashi, research fellow at Dai Nippon Printing (DNP); and Aki Fujimura, chief executive of D2S. What follows are excerpts of that conversation. To view part one, click here.

SE: When will chipmakers insert EUV technology?

McIntyre: The foundry N7 node is where it will see its first use, but it will be as a later insertion—maybe not the up-front solution. It will be a mainstream requirement for N5.

SE: Photon shot noise appears to be a big issue with EUV. A photon is a fundamental particle of light. Photon shot noise involves the variation of the number of photons in a given lithographic process. Why is this important for EUV?

Levinson: It really comes about because we measure our doses in energy. An EUV photon has 14 times more energy than an ArF photon, so for the same dose as we call it, I have 14 times fewer photons with EUV lithography. And the volume over which I’m measuring how many I have is shrinking, as I’m going to the next node. That’s why it has come up.

SE: Variations in the number of photons can impact the EUV resists during the patterning process. It can cause unwanted line-edge roughness (or LER, which is defined as a deviation of a feature edge from an ideal shape). LER has become problematic for EUV, right?

McIntyre: Line-edge roughness is clearly one of our biggest challenges in inserting and driving down further with EUV. You need to figure out a way to reduce and mitigate the roughness. Are we going to get down to 10% roughness control in a litho tool? Probably not. So it’s going to require the combination of litho with other unit processes to help smooth out these lines and get down to at least an acceptable level of roughness by smoothing the edge. There are some other tricks out there, such as deposition, atomic layer etch and directed self-assembly. They all could be ways to help get down to the final roughness values. And in addition, we may have to convince the electrical guys that they can’t get what they used to get in terms of roughness. Maybe they can live with a little bit more. And further downstream processes can absorb some of the roughness challenges that we’re stuck with.

Fig. 1: Line edge roughness. Source: Fractiliia

SE: How much of the LER problem is caused by the EUV scanner versus the resist?

Levinson: One of our engineers presented a paper at the recent SPIE conference. She basically analyzed what fraction of the roughness comes from photon shot noise and how much comes from the resists. For state-of-the-art EUV resists, it’s 60% photon shot noise and 40% materials. And then what we tried to do is optimize it. What’s interesting is when you optimize it, you have to increase your photons. Once do you that and re-optimize, we end up pretty much back with the same ratio of 40:60.

McIntyre: They are all interconnected. Is it the resist’s fault or is it the tool’s fault that it doesn’t have enough photons? You can blame it on each all day. But ultimately, it’s a combined effort. From the resist side, there’s been very good progress. Two years ago, we started to see a bunch of different techniques out there, not just your standard chemically amplified resists. There are a variety of techniques that involve inserting metals into the resists in different ways. At Imec, we had an initial screening and looked at a whole bunch of different techniques. Currently, we are trying to drive two of them to meet the needs for the industry. There are the traditional CAR resists. But also, there is the metal oxide resist with Inpria. At 16nm half-pitch, they are very similar in terms of dose and roughness. They both see micro-bridging. They are kind of about neck and neck. If you go further down in resolution, maybe 13nm half-pitch, then the metal-oxide resist seems to show a little bit of an advantage in terms of pure resolution. But the fact that they are kind of similar, it might tell you something about the relative effect of the tools, compared to the resists. They are very different platforms and different in terms of the physics.

Fig. 2: Etched pillars. Source: Imec.

SE: Let’s move to 193nm immersion lithography and multiple patterning. With this technology, we are moving from 16nm/14nm to 10nm and perhaps 7nm. What are the challenges?

Hayashi: On the mask side, you separate or split the mask in multi-patterning. Currently, overlay accuracy and layer-to-layer accuracy are very critical. The CD uniformity requirement is very critical. So now the industry is talking about edge placement error. That combines the overlay error plus the CD error. You want to control the final edge placement position with both overlay accuracy and CD accuracy. So currently the industry has a tough time making good masks with good yields. That’s a challenge. In addition, for these critical requirements, metrology is now on the boundary of the limit. We need, for example, 0.3nm repeatability in the metrology tool. It’s quite difficult to get this type of system.

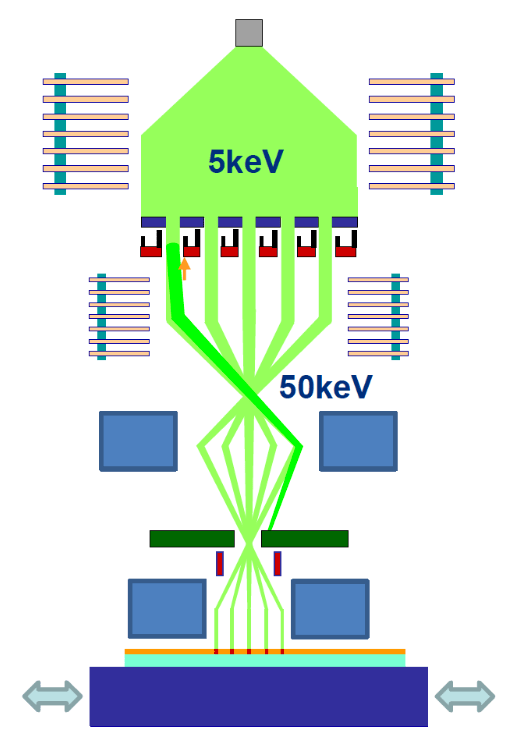

SE: Let’s continue on the mask side with today’s optical photomasks. Traditionally, mask makers use single-beam e-beam tools to pattern or write the features on a photomask. But the write times continue to increase for the most complex masks. Now, however, IMS has rolled out the world’s first multi-beam mask writer. What does multi-beam bring to the party?

Fujimura: Let’s say somebody wants to write something that would take 60 hours on today’s mask writers. Then the mask shop says, ‘It’s probably not wise to do that for production.’ But those types of masks you can do it with a multi-beam mask writer. Multi-beam will enable a whole new set of different kinds of masks that you couldn’t imagine writing before.

Hayashi: EUV is making progress. In addition, many people still want to extend optical lithography. In both cases, pattern complexity is an issue. Fortunately, we expected that. So about 10 years ago, we started evaluating multi-beam mask writer technology. Today at DNP we have one multi-beam mask writer system. We will start production with this system soon. We can use a multi-beam writer for EUV masks or to extend optical masks. The multi-beam system has a constant writing time. It’s not dependent on pattern complexity. The writing time is about 10 hours per mask. We already have confirmed that the position accuracy of the beam is better than the current VSB system. Maybe we can get good overlay accuracy, even for multiple patterning optical masks.

Fig. 3: Multi-beam uses many beamlets in parallel. Source: IMS Nanofabrication AG

SE: What else?

Hayashi: Even for full-chip ILT features, the writing time is the same using multi-beam.

Fujimura: From my perspective on the computational side, I am inspired by the multi-beam methodology of basically using pixels to represent things. We see a parallel here. D2S is a GPU acceleration company. Multi-beam machines are agnostic to write times. Write times are agnostic to the shape complexity when you use GPU acceleration and methods in computing. It doesn’t matter what shape you are given. Your complexity of computing is a function of how small those pixels are. All of these things are creating massive changes over the next three to four years. We’ve been predicting it for maybe 10 years now. But it’s now happening. And the pace of change is accelerating quite a bit.

SE: Chipmakers have moved down the scaling path with various multi-patterning schemes in the fab. This will get us to 7nm. But let’s say EUV doesn’t happen at 7nm and/or 5nm. Can we extend 193nm immersion to 5nm using self-aligned octuple patterning (SAOP)?

Fried: We’ve seen demonstrations of SAOP or self-aligned octuple pattering. It’s been executed shall we say, but maybe not well. The key challenge to all of this comes back to edge placement error now. And when you talk about aligning a via, as an example, to one of those lines that was patterned from the eighth frequency multiplication of a self-aligned mask, what does edge placement error mean? You have to get that via in the line or a block. Then, you cut one of those lines. You now have an EPE that is governed by the CD and the overlay of the block exposure. But you also have to factor in all of those depositions, etches and cleans in that multi-patterning module. So now, you have 30 or 40 processes that are contributing to the final edge position of a line, and then you have to cut it. So you can do SAOP. You can make gratings out of SAOP. But the variation of cutting, and the variation of any other level interacting with that, is really challenging. So if we are forced to go down the path of SAOP or even further, what will dig us out of that hole is a lot of new self-alignment techniques.

McIntyre: It’s hard to imagine in a full immersion world that we use SAOP. To do SAOP with immersion cuts and blocks is massively expensive. So, it seems that if we are ever going to get to the point where sub-20nm pitches are useful, EUV has to happen in order to create cuts and the blocks to make it all worthwhile. Could you do N5 with all immersion? Maybe. But it’s probably cost probative to have it make sense.

Fried: We are not that far away from doing what is considered cost prohibitive, such that you have to essentially yield higher in your next technology to make the same amount of money as in the previous one. We are not far from it, so there is not a lot of room.

SE: Today, there is a lot of talk about edge placement error (EPE). EPE is basically the difference between the intended and the printed features of an IC layout. Have we hit the boiling point in EPE?

Levinson: The difficulty has gone up astronomically. You have multiple contributions to overlay. The way we fix things is that we take each one of them and improve them a little bit. It adds up to a better number at the end of the day. The problem is that we are now asking to improve this number from 5 angstroms to 4 angstroms. Just trying to measure that you’ve done it successfully is a huge challenge.

Fried: EPE has always been there. For many generations, it was simple enough to abstract to CD and overlay. If you manage CD and overlay, you basically reached the edge placement you needed. But once you get into multi-patterning and much more complicated structures, it’s not just CD and overlay anymore. We have to stop just thinking about CD and overlay and go back to what it really is—edge placement error. We can’t simplify it anymore.

McIntyre: The other aspect is the control across the wafer lot-to-lot. Even if you have self-aligned processes, there is still an incredible amount of control you need to have. That involves pulling together all of the data that you have from your various metrology sources, such as overlay, CD and OCD. Then you put it in some type of compute engine. It figures out in real-time how to go back and tune all of the knobs that you have available on your scanner and etching tool in order to keep this level of control on the wafer lot-to-lot. Of course, we’ve always done this. But now it is getting more sophisticated and important.

SE: As the industry moves to 10nm, 7nm and beyond, what does this mean in terms of cost from your vantage point?

Hayashi: It is quite difficult for the industry to keep investing for the most advanced tools to support these types of advanced masks.

Fried: My suspicion is that the design cost to enter an advanced technology is increasing at a much higher rate than the mask cost for a full product set.

Levinson: I was given a phrase by one our engineers. What he noted is this: ‘As expensive as the masks are, they are a tax on the design costs.’ I mean you are talking under 10% or around 10%. It’s not cheap, however.

Fried: We are talking about hundreds of millions of dollars to design into an advanced technology right now.

Fujimura: That’s for the original design. That’s been true for a long time, so people make derivative designs. And those design costs are lower. They try to take advantage of re-using the components, even in the same node. But some can’t do that anymore, because the mask costs are higher.

Levinson: It comes back to what we were talking about earlier and that is, ‘Is there a market?’ As long as you have a market that matches up to the design costs and all of the other costs, then you don’t have a problem. Now, you need to have a market that’s so huge for each one of these products.

Related Stories

Why EUV Is So Difficult

One of the most complex technologies ever developed is getting closer to rollout. Here’s why it took so long, and why it still isn’t a sure thing.

Multi-Patterning Issues At 7nm, 5nm

Variations in different masks, alignment problems and the physical limits of immersion add up to serious issues at 7nm and 5nm.

Patterning Problems Pile Up

Edge placement error emerges as the top issue at advanced nodes.

Great read. This does bring out in sharp relief, the comparison between immersion litho and EUV.

It doesn’t seem practical to consider features down to 10-15 nm, due to the graininess of the lattice constant. I think 10nm node where we are now is already a practical limit.

Intel is using SAQP for its 10nm. It does not appear their mask count is blowing up as fast as others have predicted, and they themselves have pointed this out. slide 29: https://newsroom.intel.com/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/03/Ruth-Brain-2017-Manufacturing.pdf