30 facilities planned, including 10/7nm processes, but trade war and economic factors could slow progress.

China continues to advance its foundry industry with huge investments in new fabs and technology, despite trade tensions and a slowdown in the IC market.

China has the most fab projects in the world, with 30 new facilities or lines in construction or on the drawing board, according to data from SEMI’s World Fab Forecast Report. Of those, 13 fabs are targeted for the foundry market, according to SEMI. The remaining facilities are geared toward LEDs, memory and other technologies.

As before, China’s foundry industry is split into two categories—multinational and domestic vendors. Until recently, both groups used older technology. But Taiwan-based TSMC recently moved into 16nm finFET production in China, while SMIC this year hopes to become the first domestic foundry vendor to enter the 14nm finFET race. SMIC’s move would put it on par with some of its foreign rivals. In addition, SMIC has obtained $10 billion in funding to develop 10nm and 7nm.

Still, it’s doubtful that China will build all 30 fabs. It’s also unclear whether it can develop 10nm or 7nm. And for the foreseeable future, the majority of China’s foundry production remains at 28nm and above.

But armed with billions of dollars, the China government is determined to develop the nation’s IC industry to combat a trade gap. China has a sizeable domestic IC industry, but the nation imports the vast majority of its chips from foreign suppliers. In response, the China government for some time has been investing in its domestic IC industry. It also has lured several multinational chipmakers to build memory and foundry fabs in China.

Those efforts are paying off, but the current IC slowdown, coupled with U.S.-China trade tensions, is causing some headwinds for both memory and foundry vendors in China. Some chipmakers are decelerating their fab expansion plans there, while others are delaying their projects.

Still, some foundry vendors are expanding in China. While some are trying to move to the high end, most are stuck at more mature nodes, where the competition is fierce within China and elsewhere. This is especially true at one popular node. “They are all backed up, especially at 28nm,” said Bill McClean, president of IC Insights. “The foundries talk about the overcapacity situation at 28nm lasting a couple of years. They are not talking about a couple of quarters. They are talking years.”

All told, China remains a vibrant foundry market. The domestic foundry vendors continue to gain steam, although they won’t dominate the landscape anytime soon. In total, China-based companies’ share in the foundry market is expected to reach only 9.2% in 2018, up from 9.1% in 2017, according to IC Insights.

Nevertheless, there are a number of major foundry events in China. Here’s the latest:

Made in China and trade wars

Over the years, China has unveiled various initiatives to advance its domestic IC industry. With help from foreign concerns, China launched several joint chip ventures in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by the emergence of Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), China’s largest foundry player, in 2000.

Around that time, OEMs began to move a large percentage of their production to China. Demand for ICs grew, and China eventually became the world’s largest market for chips.

However, China’s IC industry could only satisfy some demand, and the nation was forced to import most ICs from foreign suppliers. By 2015, China amassed a $150 billion trade deficit in ICs alone, according to Gartner.

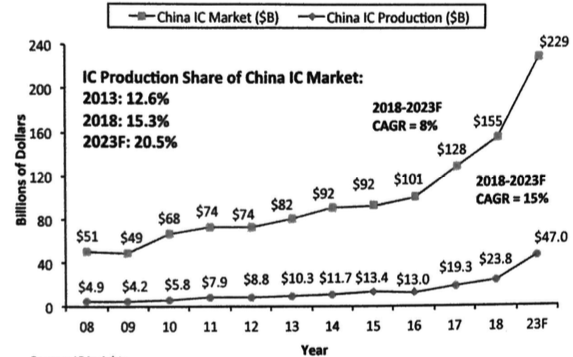

In 2013, China consumed $82 billion, or 30%, of the world’s chips, according to IC Insights. But IC production in China was $10.3 billion in 2013, which represented only 12.6% of the world’s chip production, according to the firm.

At the time, China also found itself behind in IC technology. For one thing, it was late in modernizing its IC industry. In addition, the United States and other nations imposed strict export control regulations for China, which prevented equipment vendors from shipping the latest gear into China. Recently, many export controls have been relaxed in China.

In response, the Chinese government unveiled a new plan in 2014, dubbed the “National Guideline for Development of the IC Industry.” The plan was designed to accelerate China’s efforts in 14nm finFETs, memory and advanced packaging. To help its cause, China poured billions of dollars into the arena.

The overall goal of these and other programs in China is to reduce its dependency on foreign suppliers. “That’s the issue with China. These projects are not driven by market demand. It’s driven by policy. They want to build capacity to be independent from overseas vendors,” said Clark Tseng, director of industry research and statistics at SEMI.

Then, in 2015, China launched another initiative, dubbed “Made in China 2025.” The goal is to increase the domestic content of components in 10 key areas—IT, robotics, aerospace, shipping, railways, electric vehicles, power equipment, materials, medicine, and machinery.

As part of those efforts, China hopes to become more self-sufficient in ICs. It wants to increase its domestic IC production from less than 20% in 2015 to 70% by 2025, according to IC Insights.

To accomplish those goals, China would not only develop its own technology, but it also wants to acquire foreign companies to gain access to technology.

It acquistion strategy hasn’t worked out as planned, at least for now. While China has purchased several small foreign IC vendors, its strategy was derailed in 2015 when it tried to acquire U.S.-based Micron Technology. The deal, which would have given China a vast portfolio of memory technology, was scrapped due to U.S national security concerns.

Since then China has made some progress in ICs, but it has fallen short of its goals. It still imports most of its ICs. In 2018, China produced 15.3% of the world’s chips, up from 12.6% in 2013, according to IC Insights.

Fig. 1: China’s IC market vs. production trends. Source: IC Insights

That’s the least of China’s problems. Last year, the Trump administration started a trade war with China for a couple of reasons. First, China has a massive trade surplus with the U.S. And second, U.S. companies have been the subject of IP theft in China, which has largely gone unchecked, according to the Trump administration.

In response, the U.S. last year slapped a 10% tariff on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods. China retaliated with a 10% tariff on $60 billion of U.S. imports. The U.S. said it wants to increase the tariffs on Chinese goods to 25%, but that action has been postponed. Then, in a separate measure, the U.S. last year restricted exports of fab equipment to Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co. (JHICC), a Chinese DRAM hopeful. JHICC faces some legal and IP issues.

All told, SEMI estimates that these tariffs will cost semiconductor companies more than $700 million annually. “Trade disputes can quickly spin out of control,” pointed out Joanne Itow, managing director of manufacturing at Semico Research. “Partnerships, purchasing and inventory levels are all impacted by increased levels of uncertainty, and we already are seeing companies develop contingency planning scenarios.”

Plus, the trade issues have rattled China. “China is kind of backing off that 2025 goal. Part of that might be due to the trade issues. This ‘Made in China’ campaign and these aggressive targets really put foreign governments on alert with China,” IC Insights’ McClean said.

Still to be seen, however, is whether China will continue to pursue its aggressive goals. Amid the geopolitical issues, demand for chips is slowing in China. This is impacting a growing number of vendors, such as Apple, Intel, Texas Instruments and TSMC.

Citing a slowdown in memory and other factors, chip sales in China are expected to grow by only 3% in 2019, compared to 21% growth in 2018, according to IC Insights. In total, the worldwide chip market will grow by 2% this year, the firm noted.

There are other ominous signs. Pure-play foundry sales in China reached $10.69 billion in 2018, up 41% over 2017, according to IC Insights. In 2019, though, foundry sales in China are expected to slow to about 10%. “Some of the Chinese fabless companies are doing well. HiSilicon is one example. They are basically the main supplier for Huawei. And Huawei is doing well in the smartphone business,” McClean said. “In the foundry space, however, the growth in China is a little misleading. Especially in the first half of 2018, a lot of that growth was driven by cryptocurrency designs. Bitcoin took a tremendous hit last year. That’s taken away a lot of the steam in the China market.”

Still, China continues to build up foundry capacity. “Out of the 30 fabs and lines starting construction in 2018 and beyond, 13 are for foundry,” said Christian Dieseldorff, an analyst at SEMI. “As of the end of 2018, our data showed an installed foundry capacity of 1.3 million wpm in 200mm equivalents in China. Worldwide is about 7 million wpm. This includes IDM foundry capacity.”

The figures include both 200mm and 300mm fabs. In total, there are six 200mm facilities in the works in China, according to Dieseldorff.

From the equipment perspective, meanwhile, it’s a mixed picture. Last year, SEMI reduced its projections for fab equipment spending in China for 2019, from $17 billion to roughly $12 billion. So, in 2019, fab equipment spending in China is expected to reach $11.96 billion, down 2% over 2018, according to SEMI.

“We revised our forecast for 2019 and we still expect pretty healthy growth for China in 2020. We scaled down some of the capacity ramp-up plans in the next two years. But still, there are a lot of memory projects in China, such as Samsung, SK Hynix and even Intel. The investment in China is still strong,” SEMI’s Tseng said. “SK Hynix will invest more this year in China compared to Samsung. This is because they have a new fab in Wuxi.

“The reason why we scaled down the forecast is the China part. We don’t think they will ramp up as fast as they announced. There is a potential that the DRAM project in Fujian will essentially stop. The Hefei project has been very low profile. Overall, the progress is slower than what they announced. It’s also slower than what we expected,” Tseng said. The SEMI analyst is referring to DRAM hopeful JHICC, which is based in Fujian. Innotron, another China DRAM vendor, is located in Hefei.

Others see similar patterns. “The domestic semiconductor companies have been spending quite a bit. And the business was up at all major equipment suppliers in 2018,” said Risto Puhakka, president of VLSI Research. “Now, the indications are that it’s going to slow down like the rest of the industry. In China, you have two different groups. One, you have the domestic Chinese companies. Then, you have the multinationals. The multinationals, in a very large way, won’t be increasing their capital spending. Then, you have the domestic companies. Their projects are not finished by any measure. They will spend some, but it looks like they obtained a fair amount of equipment last year, roughly $5 billion. They have plenty of tools for now.”

Most see flat equipment growth for 2019. “I don’t expect the overall wafer fab equipment market from China to change significantly between ’18 and ’19,” said Oreste Donzella, senior vice president and chief marketing officer at KLA. “The mix is different. We see more foundry and less memory. We see more foreign investment and less local.”

Regarding the IC market as a whole, Donzella said: “For memory, what we are seeing right now is a definite slowdown. I see a CapEx decrease in ’19 for DRAM after an incredible year. In NAND, it will be modestly down in ’19. We believe foundry will go up. The question is how much will foundry go up.”

Multinational foundry landscape

There are several multinational foundry vendors in China. Last year, TSMC had a big year, thanks to a boom cycle in cryptocurrency. TSMC makes chips for the cryptocurrency systems firms in China and elsewhere.

Now, the company is suffering from the bust in Bitcoin. In its fourth-quarter results, TSMC posted mixed results with a weak outlook due to a slowdown in smartphones and cryptocurrency.

It’s unclear if this will impact TSMC’s fab plans in China. For years, the company has operated a 200mm fab in Shanghai.

Last year, TSMC began ramping up 16nm finFETs in a new fab in Nanjing. The 300mm fab is producing 10,000 wpm with plans to move to 20,000 wpm by year’s end.

Fig. 2: Major IC manufacturers in China Source: IC Insights

FinFETs represent a big leap for China. For years, chip production within China has been limited to traditional planar transistors at 28nm and above. FinFETs are used at 16nm/14nm and beyond. In finFETs, the control of the current is accomplished by implementing a gate on each of the three sides of a fin.

TSMC’s Nanjing fab is in the first phase with three other phases in the works. Originally, the company planned to move 7nm into a proposed second fab in Nanjing at some point, according to sources. Now, TSMC is rethinking its plans, targeting 16nm or 12nm for the second phase, sources added.

Not all processes are at the leading edge. For example, UMC has been producing chips in a 200mm fab in Suzhou for several years. UMC plans to expand this fab amid a worldwide shortage of 200mm capacity.

“That’s still on schedule,” said Jason Wang, co-CEO of UMC, in a recent conference call. “And we still have confidence in terms of our 8-inch outlook.”

Meanwhile, in 2017, UMC moved into production in a 300mm fab venture in Xiamen. The fab is ramping up 40nm and 28nm.

Demand for 40nm is steady, but 28nm is engulfed in an oversupply mode for all foundry vendors. “28nm will remain flat. 28nm may experience (an) overcapacity situation for the next years,” Wang said.

Meanwhile, GlobalFoundries is building a 300mm fab in Chengdu. Previously, the goal was to develop 180nm/130nm processes in the fab. Last year, though, the company changed its plans, targeting the fab for its 22nm FD-SOI technology, dubbed FDX. It has not provided a timeline for the completion of the fab.

GlobalFoundries also is ramping up 22nm FD-SOI in a German fab. Nonetheless, the company sees growing interest for FD-SOI in China. “FDX technology is particularly well-suited to the China market, and we continue to see strong potential for its up-take in segments, such as 5G, IoT and edge computing,” said Tom Caulfield, chief executive of GlobalFoundries.

In addition, contract manufacturing giant Foxconn is in talks to build a 300mm fab in Zhuhai, according to reports. The fab, a joint venture between Foxconn and Sharp, would be used for both captive and foundry purposes. Foxconn has yet to make an official announcement.

Domestic foundry vendors

China also has more than a half-dozen domestic foundry vendors. SMIC is the largest one. The Huahong Group is another foundry player in China. Other vendors include ASMC and CSMC.

2019 is a major test for SMIC, the most advanced domestic foundry in China. SMIC’s most advanced technology is 28nm, although it has been struggling with its yields in this arena.

In comparison, TSMC introduced 28nm a decade ago. The foundry currently is ramping up 7nm, with 5nm and 3nm in R&D.

GlobalFoundries, Samsung and UMC offer 28nm, and they are ramping up 14nm. For now, though, GlobalFoundries and UMC have stopped development beyond 14nm and/or 12nm.

Samsung is ramping up 7nm and other nodes, with 3nm in R&D. And Intel continues to ramp up 14nm, with 10nm in the works. (Intel’s 10nm is roughly equivalent to 7nm at commercial foundries.)

China is behind in process technology. So in 2015, SMIC, Huawei, Imec and Qualcomm formed a joint R&D chip technology venture in China with plans to develop 14nm finFETs by 2020.

With the technology, SMIC will shortly enter the 14nm finFET market. “We are walking towards risk production in the second half of (2019),” said Liang Mong Song, co-CEO of SMIC, in a recent conference call.

Still to be seen, however, is whether SMIC can produce finFETs in volume with good yields. “With more knowledge and process module recipes available on finFETs, it is only a matter of time when SMIC will get it developed,” said Samuel Wang, an analyst with Gartner. “Time to market is critical. If early, they can be successful. If it’s too late, then it’s more challenging.”

If SMIC can produce 14nm finFETs in volume, it would put the company on par with several foreign rivals. Near-term, though, SMIC’s 14nm capacity will remain small.

SMIC isn’t standing still. With funding from the China government, it plans to develop more advanced processes in a new 300mm fab. “SMIC is getting $10 billion to build capacity for 14nm, 10nm and 7nm. They will have capacity for 70,000 wafers a month by Q4 in 2021,” said Handel Jones, chief executive of International Business Strategies (IBS). “The building is huge. They have bought some equipment, but nothing significant yet.”

SMIC faces some challenges. 14nm finFETs are difficult to develop, but 7nm represents a quantum leap. At each node, the technical challenges and costs escalate, and there are fewer customers that can afford these nodes due to soaring IC design costs. The processes are also becoming more complex, making it difficult to find the killer defects that impact yield. In addition, patterning remains challenging. And at some point during 7nm, some hope to insert extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, a move that brings more risk into the equation. That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Besides SMIC, meanwhile, the Huahong Group is also a player in China. HHGrace and Hua Hong Semiconductor, two foundry vendors within this group, provide 200mm foundry services. Hua Hong also is building a new 300mm fab for mature processes in Wuxi.

Shanghai Huali, another member of the Huahong Group, has a new 300mm fab in the works with plans to ramp up 28nm. At some point, the company is targeting 14nm.

One of the newer foundry players is CanSemi Technology, which is building a 300mm fab in Guangzhou. At one time, CanSemi was led by Richard Chang, formerly president of SMIC.

CanSemi’s future is unclear as its leader has departed. “CanSemi seems to be in existence,” Gartner’s Wang said. “Richard Chang has left to start a new company.”

Put in perspective, China’s IC industry has been dynamic with sizzling growth. Now, though, China faces an economic slowdown, not to mention a trade war, so perhaps the IC party will be postponed.

Related Stories

Good info about china semiconductor market