Edge placement error emerges as the top issue at advanced nodes.

Chipmakers are ramping up 16nm/14nm finFET processes, with 10nm and 7nm now moving into early production. But at 10nm and beyond, chipmakers are running into a new set of problems.

While shrinking feature sizes of a device down to 10nm, 7nm, 5nm and perhaps beyond is possible using current and future fab equipment, there doesn’t seem to be a simple way to solve the edge placement error (EPE) issue.

EPE basically is the difference between the intended and the printed features of an IC layout. It involves patterning of tiny features in precise locations. For example, a feature could be a line, and that line has right and left edges. But in a device, the line and its edges must be precise and placed in exact locations. Then, a contact may land on that line in the device. If these are not precise and exact, that results in misalignment, or an EPE. And if one or more EPE issues crop up in the production flow, the device is subject to shorts or poor yields, which could cause the entire chip to fail.

“That’s really what gates Moore’s Law,” said Richard Wise, technical managing director at LAM Research. “It’s not so much about whether you can shrink the features. You can always shrink the feature size. The real challenge is putting things where they belong with variability. And the EPE eats into our budget for variability.”

It doesn’t matter if a fab uses optical lithography tools with multiple patterning, extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography or other technology types. The overall goal is to put the features in the right places, and avoid EPEs. This goes for patterning all parts of the device.

EPE sounds trivial, but the challenges are escalating and piling up at each node. The problems are caused by a host of issues in the fab.

“This basically involves the precision of edges on the features” said Regina Freed, senior director of product marketing for patterning technology at Applied Materials. “It becomes important when you are starting to align multiple layers on each other. But our features have shrunk a lot. The total error budget has gone up because we’ve added a lot of process steps. So, we get difficulties in scaling because we can’t place the features exactly where we want them anymore.”

It’s still possible to pattern the features in exact places at advanced nodes, but the process becomes more expensive and difficult. The margin for error is down to single-digit nanometers with angstrom-level tolerances. Needless to say, the industry needs to keep a close eye on the issues behind EPE and the potential solutions.

What is EPE?

Nearly two decades ago, lithographers devised a term called edge placement error, which involves several arcane patterning and metrology concepts. But the topic began to heat up at the 22nm/20nm logic node, when chipmakers moved from single to multiple patterning techniques in the fab.

Patterning is one of the key parts of the IC manufacturing flow. In patterning, a lithography scanner exposes light in select places on a wafer, creating tiny patterns or features that make up a device. Over the years, lithography tool suppliers have developed light sources with shorter wavelengths, which in turn can print smaller features.

Today, chipmakers use 193nm wavelength lithography to print features on a wafer. In reality, though, 193nm lithography reached its limit at 80nm pitch or 40nm half-pitch.

To extend 193nm lithography at 20nm and beyond, chipmakers moved from single patterning to multiple patterning. Single patterning is a relatively straightforward and mature process. “Single patterning is the creation of patterns in a film by use of a single lithographic exposure,” said Harry Levinson, senior fellow and senior director of technology research at GlobalFoundries.

In multiple patterning, “the original mask shapes are divided between two or more masks,” said David Abercrombie, program manager for advanced physical verification methodology at Mentor Graphics. “Each mask is then printed separately, eventually imaging the entire set of originally-drawn shapes onto the wafer.”

Multiple patterning enables the industry to extend IC scaling, but it also increases the complexity. A 28nm device has 40 to 50 mask layers. In comparison, a 14nm/10nm device has 60 layers, with 7nm expected to jump to 80 to 85. 5nm could have 100 layers.

On top of that, the device has migrated from a planar to a 3D-like finFET structure starting at 22nm, a move that presents several new and difficult challenges in the fab, namely patterning. “The reality is that when you are looking at a device, the thing that really matters is how you line up one edge relative to the other one,” said Michael Lercel, director of product marketing at ASML. “For example, when you are thinking about a via landing on a line, it’s a question of where do the edges land.”

Here’s the challenge: The device features, such as lines, contacts and vias, become smaller at each node. Each feature and its edges must be precise and placed on the exact locations on each layer. And they must be exact and properly aligned with the other layers.

But if the features aren’t precise, the critical dimensions (CDs) of a device are misaligned. And if the features on the various layers are not exact and aligned, it causes what’s called an overlay error. Basically, overlay is pattern-to-pattern alignment among the various layers on the device.

In the planar and single patterning era, lithographers were mainly worried about two metrics—CD uniformity and overlay errors. To determine these metrics, a chipmaker might use a CD-SEM and/or an optical metrology tool to measure the CDs of the features. A separate overlay metrology tool would measure overlay. Then, you take these two separate measurements—CD uniformity and overlay—combine them and add them up, resulting in a numerical figure that represents EPE or the EPE budget.

Fig. 1: Shrinking dimensions exacerbate EPE issues. Source: ASML

At advanced nodes, though, it’s more complex. Generally, EPE is sub-divided into two categories—global and local effects, according to Ofer Adan, global product manager and a member of the technical staff at Applied Materials, in a presentation at IEDM.

Local EPE issues are caused by placement errors in the production flow. Meanwhile, global EPE is caused by the following issues—CD uniformity; intra-layer overlay; layer-to-layer overlay; and line-edge roughness (LER)/line-width roughness (LWR), according to Adan.

So in simple terms, EPE is equal to the combination of all of these factors—CD uniformity, overlay (intra-layer and layer-to-layer) and LER. And if that isn’t enough, you also add fab variations and random variations in the equation.

Of those, LER/LWR are becoming more problematic. During the patterning process, the features are not perfectly smooth. This is sometimes called pattern roughness or LER and LWR. LER itself describes the amount of variation on the edges of the features.

LER is a big problem with EUV. The issues involve the interaction between the EUV scanner and the resist. The interactions cause random variations or stochastics.

What causes EPE? Previously, EPE was mainly caused by lithography-based overlay errors and other issues. At advanced nodes, though, EPE is caused by lithography as well as process-induced issues. In other words most, if not all, of the fab tools in the flow can cause EPE, making it difficult to pinpoint the exact problem.

EPE is also difficult to measure. For local and global EPE effects, chipmakers must take more complex measurements. “When devices were simpler and predominately two dimensional, you could analyze individual layers in terms of their CD or overlay performance individually. You were able to boil the EPE issues down to single level metrics,” said David Fried, chief technology officer at Coventor.

“Now, especially with multi-patterning and the complexity of devices, you can’t treat individual layers as simple anymore,” Fried said. “You can’t just consider the CD uniformity or the overlay registration error for the individual layers in order to specify the actual structural behavior of the technology.”

All of this presents more headaches in the fab. “The difficulty has gone up astronomically,” GlobalFoundries’ Levinson said. “You have multiple contributions to overlay. The way we fix things is that we take each one of them and improve them a little bit. It adds up to a better number at the end of the day. The problem is that we are now asking to improve this number from 5 angstroms to 4 angstroms. Just trying to measure that you’ve done it successfully is a huge challenge.”

For example, in a given portion of a design at 40nm, there might be six tiny lines with spaces in between. Each line might have a width of 20nm. The pitch between the lines is 40nm. At those dimensions, you must place and align different features, such as contacts, vias and other lines, in exact places.

And the margin for error is becoming smaller at each node. Generally, the EPE budget is roughly a quarter of the pitch of a given feature size. For example, a 40nm feature has a 10nm EPE budget. Today, though, the feature sizes are 20nm and below, which means the EPE budget is a mere 5nm or smaller for a single layer. Moreover, the industry must reduce EPE by some 30% to achieve the 5nm node, according to some experts.

In the fab

So how do chipmakers solve the EPE problem? Each chipmaker has a process flow and a way to control EPE, both of which are proprietary and closely guarded secrets.

One expert presented a hypothetical flow in the fab. “First, you have to measure and control EPE as best as possible,” said Greg McIntyre, director of the Advanced Patterning Department at IMEC. “There are a handful of different solutions out there. They are trying to find ways to take information from a variety of sources. Then, you put the information in a computational engine. It tells you how to tune all of the knobs on your tools.”

Generally, with today’s finFET technologies, the manufacturing process starts with patterning. In the multi-patterning flow, chipmakers implement a two-step process—lines and cuts.

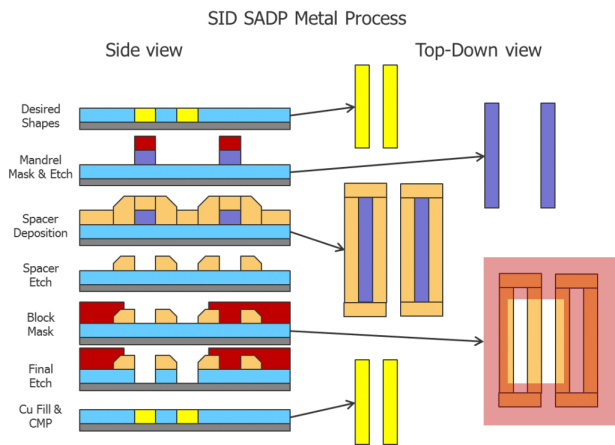

First, tiny lines are patterned on one layer of a device. For this, chipmakers use a technique called self-aligned double patterning/quadruple patterning (SADP/SAQP). SADP/SAQP uses one lithography step and additional deposition and etch steps. Then the lines are cut into intricate patterns. For the cuts, chipmakers use SADP/SAQP, double patterning or triple patterning. Double patterning is sometimes called litho-etch-litho-etch (LELE). Triple patterning involves LELELE.

During these processes, problems sometimes can surface. “If you do SADP or SAQP, there are a lot of deposition and etch steps involved. They cause various issues, like LER, pitch walking and local CDU variations,” Applied’s Freed said. “Part of it is litho. Part of it is deposition. Part of it is etch. It’s becomes a complicated equation to solve.”

Fig. 2: SADP Metal Process where spacer is dielectric. Source: Mentor Graphics.

There are countless examples of potential problems. For example, the process can cause a poor sidewall in a structure. “In reality, for most of the materials we use today in production, the deposition of the spacer changes the mandrel profile. We see oxidation of stress effects of material interaction on the edge of the mandrel. Surface damage on the mandrel causes changes in the profile,” she said.

Fortunately, there are some solutions to the problem, which involve both new and traditional tools. For example, in traditional etch tools, ions bombard a surface as a means to remove unwanted materials on a surface. Etchers have various “knobs,” which can tune or control the process.

It takes a combination of technologies to address EPE. “For the things like the mandrel and spacer profile, it’s a combination of using the right materials,” Lam’s Wise said. “Some materials are more difficult to get a perfect profile than others. It’s important to co-optimize that with your etch processes. So if you understand the etch process chemistry, you can tune your materials to enable that.”

Another solution is a next-generation etch technology called atomic layer etch (ALE). Unlike conventional etch tools, which remove materials on a continuous basis, ALE promises to selectively and precisely remove targeted materials at the atomic scale. “You have fairly complex structures. And you also have structures with all sorts of surrounding materials,” said Uday Mitra, vice president of strategy and marketing for etch and patterning at Applied Materials. “With ALE, you remove the materials you want to remove with no damage.”

ALE is used for a growing number of applications in the overall patterning process. For example, etch byproducts can accumulate on the sidewalls of a device, which causes unwanted micro-loading effects. “We see ALE as being crucial for fabricating higher aspect ratios in finFETS, partly because of the reduction or elimination of micro-loading,” said Yang Pan, chief technology officer for the Global Products Group at Lam Research. “It has helped to tackle micro-loading—one of etch’s most challenging problems—while significantly reducing process complexity by allowing optimization of each step independently.”

Adjusting the knobs on the scanners, etchers and other tools are just some of the ways to control EPE. In addition, the industry is also working on a futuristic version of deposition called selective deposition. Combining novel chemistries with atomic layer deposition (ALD), selective deposition involves a process of depositing materials and films in exact places.

In one simple example, a tiny metal strip is selectively deposited between two lines on the device. In effect, the metal strip acts as a guide between the lines, preventing a misalignment in the pattern.

This sounds straightforward enough, but it’s a daunting task. Several companies are working on the technology, but it remains in R&D and is not expected until 5nm or so.

The other big hope is EUV lithography. EUV is not in production yet, but it is making progress. ASML is readying its latest EUV scanner—the NXE:3400B. Initially, the tool will ship with a 140-watt source, enabling a throughput of 100 wafers per hour (wph). A 210-watt source is in development, enabling 125 wph.

EUV promises to simplify the production flow. For example, in triple patterning with optical lithography, “you have different overlays, three different CD populations and three different CD uniformities,” ASML’s Lercel said. “We are now at basically triple the control variables. And then you start thinking about how do I meet my device performance budget.”

In theory, EUV reduces the total mask count to 60 layers or below, compared to 80 to 85 at 7nm. “EUV makes it quite a bit simpler from a process control perspective and controlling EPE,” Lercel said.

EUV doesn’t solve everything, however. “You still need good overlay, CD uniformity and OPC to meet EPE, even with EUV,” he said.

Other issues begin to crop up with EUV, including one big problem—LER. And, of course, there are other issues with EUV, such as the power source, resists and mask infrastructure.

There are other EPE solutions as well. In a recent presentation, Akihisa Sekiguchi, vice president and general manager of the Advanced Semiconductor Technology Division at Tokyo Electron Ltd. (TEL), listed several ways to control or solve EPE:

• Insert EUV lithography to reduce the number of overlay shots and errors.

• Increase or put more emphasis on process control as a means to optimize the EPE budget.

• Develop self-alignment schemes to get around the overlay issues.

This is the tip of the iceberg. “Combination of advancements in unit processes and intelligent integration are the keys to patterning,” Sekiguchi said. “Cross-field collaboration is essential in providing further innovation to support scaling.”

Related Stories

Multi-Patterning Issues At 7nm, 5nm

Variations in different masks, alignment problems and the physical limits of immersion add up to serious issues at 7nm and 5nm.

Why EUV Is So Difficult

One of the most complex technologies ever developed is getting closer to rollout. Here’s why it took so long, and why it still isn’t a sure thing.

“In reality, though, 193nm lithography reached its limit at 80nm half-pitch.”

This should be 80nm pitch or 40nm half-pitch.

Hi witeken. That’s for pointing that out. I made that change.

EPE through focus is a special problem for EUV. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extreme_ultraviolet_lithography#/media/File%3A16_nm_2-bar_EUV_asymmetry.png

I read EUV needs SMO for 7nm and beyond, and this may need to split layouts into multiple different masks, each with its own customized illumination. In other words, no advantage over immersion.